Maybe this is why some kids can read long complicated words and trip up on short easy ones

/A study of word confusability and similarity for whole-word readers

This article doesn't claim to be a valid scientific study, none-the-less it was interesting to do, and, essentially, perform as a thought experiment.

One of the things I have noticed with my own son and lots of comments from other parents of early readers, gifted and potentially hyperlexic children, is that such children astonishingly read (recognise) long complex words (such as "galaxy" and "knowledge") with ease, yet sometimes (perhaps even often) get tripped up on short "simple" words, such as "one" and "many". The question is, what is the explanation for this, as it seems to defy logic?

I happen to have a background in the field of speech recognition (in computers) and there are factors of that field which boil down to the problem of recognising and distinguishing words from each other. So, I was eventually moved to perform some kind of analysis investigating this. I don't know if this is original or even valid research, but it was fun to do.

How do early readers, read?

The first thing to be aware of is two broad types of reading (and reading-teaching) methods: phonics and "whole word" (or whole language). Phonics concerns the systematic pronunciation of the component sounds of a word to reach the whole. Whole-word does what is says on the tin: the reader either memorises or deduces the whole word in one step. (As adults we tend to read like this).

My anecdotal conversations suggest that early readers are one or the other: some early readers display/develop/self-teach a phonic approach, and the remainder, it's the whole world. (In the case of my own son, it's "whole word"). In my anecdotal evidence, the most startling early readers are "whole word" because even at age 3 or 4, obscure words of 8, 10, 12 or more letters can be decoded instantly.

Since whole-word readers essentially memorise and recognise entire words, it begs the question: given that they handle complex words with ease, why do they sometimes get tripped up on short words?

It's possible to come up with lots of theories involving visual processing disorders, dyslexic conditions, motivation (laziness) and so on. However, I theorised about a more empirical factor: if children appear to recognise short words less-well, is it simply because short words are less memorable/more confusable?

(Confusability, in various forms, is a factor we have to deal with on a regular basis in speech recognition, which prompted my thinking.)

Mr. Levenshtein, meet Dr. Fry.

Before we get to the analysis, I need to introduce two things. The first is the Fry Sight Word list. I don't seem to be able to find out much about Dr. Fry directly on the internet, but many educational websites cite the fact he created a list of the most popular and common English words in literature, originally in the 50's but since updated.

If these are the most common words that a child is going to see, then it seemed to make sense to evaluate what levels of "confusability" exists among them.

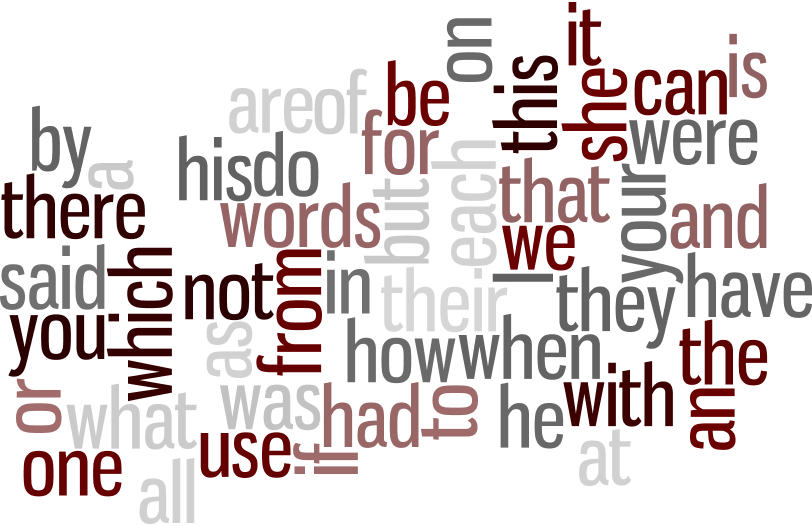

Top 50 Fry Sight words

Next we meet Mr. Levenshtein; or at least his algorithm, which provides a way to calculate the number of single character edits to transform one word into another. To put that another way, it gives a measure of word similarity - small Levenshtein distances between words means they are more textually similar than those with large distances.

We should note that Levenshtein distance only tells us about textual character difference (structure), which is certainly useful when computers are comparing words. It doesn't necessarily tell us how similar words are through the eyes of a child (e.g. geometry), but it's a good starting point.

Analysis

Analysis Summary

To perform the analysis, I took a set of "sample words" and calculated the Levenshtein distance against between each of those words and every word in the "Fry Sight List".

I compared the sample words against the full Fry list (1000 words) and also against the top 150, and plotted the distribution of Levenshtein distances obtained.

What this effectively tells us is "how similar is the target word to the most common words in the language". We might postulate that the more similar a word is to others, the more likely it could be confused - i.e. the less likely to stand out as unique. Or conversely, a greater cognitive load required to uniquely recognise it.

I plotted the results for "one" "many" "who" (all identified as "trip up" words), plus "galaxy" and "knowledge" (indentfied as easily-recalled words).

To interpret the chart, the height of each bar tells you by what amount the target word differed from how much of the Fry's list. So, for example, a 50% at marker 3 means the word differed by 3 single-character transformations against 50% of the Fry list.

Compared against 1000 top words, we see that "one" "many" and "who" are clustered around the 3,4 and 5 mark for Levenshtein distance. Indeed, this level of "similarity" captures up to 80% of the top 1000 words. In contrast, "galaxy" is typically different by around 6 - 7 letters, and "knowledge" even more different around 8 - 9 mark.

The effect is even more pronounced when comparing the sample words against the top 150 Fry words. (Again, many websites reference the claim that just 100 words make up almost half of all written material). Indeed it's likely a child doesn't compare the word they are reading against their whole vocabulary, but will prune their recognition against a vocabulary that's filtered down to a smaller, similar set. Or to put it another way, they will most consciously compare a four letter words against the 3, 4 and 5 letter words in their vocabulary, and not the 8, 9, 10 letter words, which will be discarded subconsciously.

In this case the profile of the sample words is more pronounced - the short words compare against the top 150 mainly in the 2,3,4 range (anything in 1 and 2 is certainly highly confusable). And the long, complex words now stand out as being significantly different - and thus, we presume easier to recognise uniquely within the given vocabulary.

Summary

There are of course weaknesses to this analysis:

1) it doesn't consider word geometry or font, which may make some words look more similar than others irrespective of Levenshtein distance, which considers the text only

2) The Fry Sight list is really only a arbitrary representation of the vocabulary an early reader might know. To some extent, by definition, this list is insufficient, because the words that early readers surprise their parents, carers and observers by knowing, are the long irregular words.

3) It would be useful to perform the analysis against a bigger vocabulary but of words the same length as the sample word - this might better match the process a child follows when recognising the word (pruning out the obviously non-similar words)

Notwithstanding, the comparison of sample words against the Fry Sight Word list shows statistically significant disparity in similarity between the shorter words than the longer words. At 1000 words long, the Fry Sight list offers statistical significance to the comparison.

The result is not really surprising. As we might expect, there are more short words in the vocabulary, therefore more possibility of similarity and confusion.